21st Dec 2010, 12:26

permalink Post: 921

quote:I remember at Fairford in mid 1974, a CAA test pilot (I honestly forget the gentleman's name) was taking the British pre-production A/C 101 (G-AXDN) for a special test flight.unquote

It was almost certainly Gordon Corps, possibly the finest 'engineering' test pilot I have ever worked with. After Concorde certification Gordon went to work at Toulouse wher he did most of the development flying that led to the A320 FBW system. BZ was the public 'face' of the design, but knowing the two men I have a very shrewd idea as to who did the original thinking! Perhaps Andy could confirm?

Tragically Gordon died young whilst trekking to an A300 crash site somewhere in the Himalayas

ClivL

It was almost certainly Gordon Corps, possibly the finest 'engineering' test pilot I have ever worked with. After Concorde certification Gordon went to work at Toulouse wher he did most of the development flying that led to the A320 FBW system. BZ was the public 'face' of the design, but knowing the two men I have a very shrewd idea as to who did the original thinking! Perhaps Andy could confirm?

Tragically Gordon died young whilst trekking to an A300 crash site somewhere in the Himalayas

ClivL

21st Dec 2010, 13:04

permalink Post: 922

quote:Rolls Royce did some analysis on the flight, and were amazed at how well the propulsion systems coped with some of the temperature sheers that we encountered, sometimes 4 to 5 deg's/second. They said that the prototype AFCS had been defeated by rises of only 0.25 deg's/second ).unquote

Just for the record, the intake control system was designed to cope with a temperature shear of 21 deg C in one mile (about 3 seconds)

quote:Not meaning to go off onto a (yet another) tangent; Negative temperature shears, very common at lower lattidudes, always plagued the development aircraft; you would suddenly accelerate, and in the case of a severe shear, would accelerate and accelerate!! (Your Mach number, quite naturaly, suddenly increased with the falling temperature of course, but because of the powerplant suddenly hitting an area of hyper-efficiencey, the A/C would physically accelerate rapidly, way beyond Mmo). Many modifications were tried to mitigate the effects of severe shears, in the end a clever change to the intake control unit software fixed it. (Thanks to this change the production series A/C would not be capable of level flight Mach numbers of any more than Mach 2.13, remembering that Mmo was set at 2.04).unquote

Not temperature shears, and not AICU modifications (which I see has been discussed in a later posting). But back to the 'shears':

Most of Concorde's flight testing was, naturally, done out of Toulouse and Fairford, i.e. into moderate latitude atmospheres where the tropopause is normally around 36,000 ft so that the supersonic flight testing was done in atmosphers where the temperature doesn't vary with altitude. The autopilot working in Mach hold would see an increase in Mach and apply up elevator to reduce IAS and recover the macg setting. But at the lower latitudes around the equator the atmosphere is different in its large scale characteristics. In particular the tropopause is much, much higher and can get as high as 55,000 ft. Nobody had been up there to see what it was like! Now when the A/P applied up elevator to reduce IAS it went into a region of colder air. But the speed of sound is proportional to air temperature, so as the aircraft ascended the IAS dropped alright but since the ballistic (true) velocity of the aircraft takes a while to change and since the speed of sound had dropped the Mach number was increased, so the A/P seeing this applied more up elevator and the aircraft went up and the speed of sound dropped and ........

Like solving crossword clues, the answer is obvious once you have spent some time finding it!

This phenomenon rather than temperature shears (encountered mainly over the tops of Cb clouds) was the reason for the autopilot modifications which included that clever use of autothrottle (I can use that adjective since it was my French colleagues that devised it)

And before anyone asks; yes, the same problem would relate to subsonic aircraft operating in Mach hold driven by the elevators and flying below the tropopause, but:

a) Subsonic aircraft are old ladies by comparison with Concorde in that they fly at only half the speed. At Concorde velocities even modest changes in pitch attitude can generate some pretty impressive rates of climb or dive!

b) Subsonic aircraft are normally constrained by ATC to fly at fixed flight levels - the use of elevator to control Mach number is not really an option - you have to use an autothrottle.

There was that other problem, also described in later postings, where the aircraft regularly 'rang the bell' when passing through the Vmo/Mmo corner in the lower latitudes, but this was simply due to the additional performance one got in these ISA minus conditions in comparison to the temperatures encountered around the same corner in higher temperatures.

Anyway, the flight test campaign got me my first sight of sunrise over the Arabian desert and my first trip to Asia, so it goes into my Concorde memory bank.

Just for the record, the intake control system was designed to cope with a temperature shear of 21 deg C in one mile (about 3 seconds)

quote:Not meaning to go off onto a (yet another) tangent; Negative temperature shears, very common at lower lattidudes, always plagued the development aircraft; you would suddenly accelerate, and in the case of a severe shear, would accelerate and accelerate!! (Your Mach number, quite naturaly, suddenly increased with the falling temperature of course, but because of the powerplant suddenly hitting an area of hyper-efficiencey, the A/C would physically accelerate rapidly, way beyond Mmo). Many modifications were tried to mitigate the effects of severe shears, in the end a clever change to the intake control unit software fixed it. (Thanks to this change the production series A/C would not be capable of level flight Mach numbers of any more than Mach 2.13, remembering that Mmo was set at 2.04).unquote

Not temperature shears, and not AICU modifications (which I see has been discussed in a later posting). But back to the 'shears':

Most of Concorde's flight testing was, naturally, done out of Toulouse and Fairford, i.e. into moderate latitude atmospheres where the tropopause is normally around 36,000 ft so that the supersonic flight testing was done in atmosphers where the temperature doesn't vary with altitude. The autopilot working in Mach hold would see an increase in Mach and apply up elevator to reduce IAS and recover the macg setting. But at the lower latitudes around the equator the atmosphere is different in its large scale characteristics. In particular the tropopause is much, much higher and can get as high as 55,000 ft. Nobody had been up there to see what it was like! Now when the A/P applied up elevator to reduce IAS it went into a region of colder air. But the speed of sound is proportional to air temperature, so as the aircraft ascended the IAS dropped alright but since the ballistic (true) velocity of the aircraft takes a while to change and since the speed of sound had dropped the Mach number was increased, so the A/P seeing this applied more up elevator and the aircraft went up and the speed of sound dropped and ........

Like solving crossword clues, the answer is obvious once you have spent some time finding it!

This phenomenon rather than temperature shears (encountered mainly over the tops of Cb clouds) was the reason for the autopilot modifications which included that clever use of autothrottle (I can use that adjective since it was my French colleagues that devised it)

And before anyone asks; yes, the same problem would relate to subsonic aircraft operating in Mach hold driven by the elevators and flying below the tropopause, but:

a) Subsonic aircraft are old ladies by comparison with Concorde in that they fly at only half the speed. At Concorde velocities even modest changes in pitch attitude can generate some pretty impressive rates of climb or dive!

b) Subsonic aircraft are normally constrained by ATC to fly at fixed flight levels - the use of elevator to control Mach number is not really an option - you have to use an autothrottle.

There was that other problem, also described in later postings, where the aircraft regularly 'rang the bell' when passing through the Vmo/Mmo corner in the lower latitudes, but this was simply due to the additional performance one got in these ISA minus conditions in comparison to the temperatures encountered around the same corner in higher temperatures.

Anyway, the flight test campaign got me my first sight of sunrise over the Arabian desert and my first trip to Asia, so it goes into my Concorde memory bank.

23rd Dec 2010, 08:39

permalink Post: 960

Flexure and stuff

EXWOK

Clive, I think we need your help here. I was also told, both while I was at Fairford and during one of my two ground school courses at Filton in the early 80s, that the lateral stiffeners (underneath the wing just inboard of the Rib 12 area) were added to reduce outer wing flexure and in themselves gave us a performance penalty. Can you shed any light Clive?

Best regards

Dude

Quote:

| - the whole aeroflexing of the 'A' tanks thing was something mentioned during ground school on my conversion course; I may have misunderstood or it may have been less than accurate info. |

Best regards

Dude

23rd Dec 2010, 15:16

permalink Post: 971

Quote:

|

Originally Posted by

ChristiaanJ

Clive, I think we need your help here. I was also told, both while I was at Fairford and during one of my two ground school courses at Filton in the early 80s, that the lateral stiffeners (underneath the wing just inboard of the Rib 12 area) were added to reduce outer wing flexure and in themselves gave us a performance penalty. Can you shed any light Clive?

|

I had never heard of any such stiffeners before I started reading this thread.

The wing inboard of Rib 12 was pretty stiff as was Rib 12 itself, so it didn't need stiffening there.

I don't see how tiny stiffeners like that, mounted INBOARD of Rib 12 could ever have have any significant stiffening effect on the wing OUTBOARD of Rib 12. if anyone wanted to stiffen the outer wing it would be much more efficient to do it with internal structure, so any external addition would have been some sort of panic measure and I think I would have heard of it.

The external shape of the excrescence looks to me much more like a streamlined fairing to get some sort of cable or pipe from A to B when for some reason it couldn't be passed through inside the wing. In this connection I see that the objects in question run fairly close if not along, area where one might have something going from tank 5a to 6 or 7 to 7a.

Yes there would be a small performance penalty for these fairings.

In summary I don't really know, but would need a lot of convincing that these things really were external stiffeners!

CliveL

2nd Jan 2011, 15:11

permalink Post: 1062

In earlier posts we were talking about the complex shape of the wing.

Looking through my 'archive', I've finally found this photo again... been looking for it for ages.

Kinky .... !!

Found on the net a few years ago. It's either 002 (G-BSST) or 01 (G-AXDN) at Fairford.

All Concordes have this 'kink', but the interesting thing is, that it's only visible from one very precise spot in line with with the wing leading edge. A few metres to the left or right, or forward or back, and the 'kink' disappears.

Many people are not even aware it exists.

Happy 2011 to all !

CJ

Looking through my 'archive', I've finally found this photo again... been looking for it for ages.

Kinky .... !!

Found on the net a few years ago. It's either 002 (G-BSST) or 01 (G-AXDN) at Fairford.

All Concordes have this 'kink', but the interesting thing is, that it's only visible from one very precise spot in line with with the wing leading edge. A few metres to the left or right, or forward or back, and the 'kink' disappears.

Many people are not even aware it exists.

Happy 2011 to all !

CJ

7th Jan 2011, 11:06

permalink Post: 1078

ChristiaanJ, you wrote:Is that a typo and did you mean "it made sense for

102

to get the early hybrid units."?

No. it wsn't a typo, but you may have been misled by my use of 'hybrid' by which I meant the final AICU version which most people describe as digital.It had digital law generation but analogue servo control loops. We were responsible for development of the AICU 'laws' and with Fairford being less than an hours drive from Filton it was far more convenient to do the flight testing out of Faiford so that results could be evaluated rapidly and the next day's flight test sequence planned.

CliveL

No. it wsn't a typo, but you may have been misled by my use of 'hybrid' by which I meant the final AICU version which most people describe as digital.It had digital law generation but analogue servo control loops. We were responsible for development of the AICU 'laws' and with Fairford being less than an hours drive from Filton it was far more convenient to do the flight testing out of Faiford so that results could be evaluated rapidly and the next day's flight test sequence planned.

CliveL

15th Jan 2011, 10:59

permalink Post: 1100

A Journey Back In Time !!

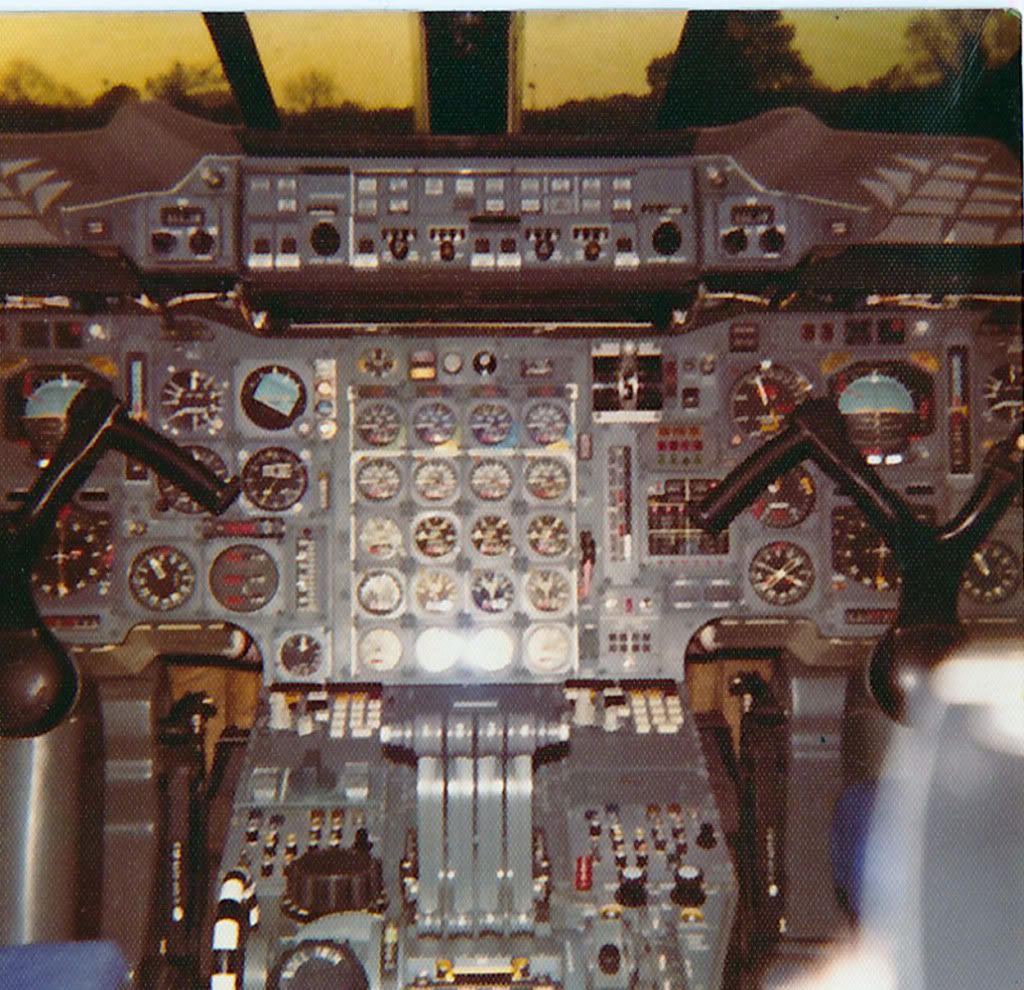

OK, here is a photo that I took at Fairford in November 1976. I'd just had my very first Concorde flight on a brand new G-BOAD, and took this flight deck photo in the hangar later that afternoon (the doors are open hence the late afternoon Cotswold sky. The point of this rather poor (sorry guys, I was young for goodness sake) photo is to look at just how subtly different the 1976 flight deck WAS.

The first thing I know EXWOK and BELLEROPHON will (maybe) notice is that originally OAD had a 'normal colour' electroluminescent light plate on the visor indication panel. (If I remember rightly (it was a million years ago chaps) when this one 'stopped lighting' we could not get a replacement and had to rob 202 (G-BBDG) at Filton; this one being the same black development aircraft colour that OAD has to this day.

The OTHER first thing that you may notice is the Triple Temperature Indicator on the captains dash panel. (The first officer had his in in similar position). These got moved around (twice in the end) when TCAS was installed in the mid-90's. It was amazing just how much equipment got moved around over the years, in order to 'shoe-horn in' various bits of extra equimpent.

The cabin altimeter here fitted just above the #1 INS CDU also got moved (to the centre consul) when the FAA 'Branniff' modifications were embodied later in the 70's. It's spot got occupied by a standy altimeter mandated by the FAA but this was removed after Branniff ceased flying Concorde; the cabin altimeter returning to it's former home. The REALLY observant will notice that there is neither an Autoland Ca3/Cat2 identifier on the AFCS panel (glued on by BA at LHR) or the famous and precision built 'Reheat Capabilty Indicator' flip down plate fitted to the centre dash panel a few years later by BA.

Also not shown here, as they were buyer furnished equipment also fitted at on delivery LHR, are the two ADEUs (Automatic Data Entry Units, or INS Card readers). These were located immediatel aft of the CDU's and were used for bulk waypoint loading ('bulk' being 9, the most that the poor old Delco INU memory could handle). These were removed in the mid 90's when the Navigation Database was fitted to Concorde INUs, and bulk loading then was achieved by simply tapping in a 2 digit code. (Hardly the elegence of FMS, but still very elegent in comparison with the ADEU's, and worked superbly). A little note about these ADEU things; You inserted this rather large optically read paper data card into the thing and the motor would suck the unsuspecting card in. As often as not the ADEU would chew the card up and spit the remnants out, without reading any data, or not even bother spitting out the remnants at all. Removing these things FINALLY when the INUs were modified was absolute joy!!

ps. When G-BOAG (then G-BFKW) was delivered in 1980 it had neither any of the Branniff mods or ADEUs fitted. (Also the INS was not wired for DME updating). This meant that obviously she could not fly IAD-DFW with Branniff but also she could not do LHR-BAH either, because of the lack ADEUs. (You could not manually insert waypoints quick enough over the 'Med', or so the guys told me. So for the first few years good old FKW/OAG just used to plod between LHR and JFK. And plod she did, superbly. She never did get the ADEUs (not necessary thank goodness when the INUs got modified) but we wired in DME updating and so she could navigate around with the best of them.

My gosh I do prattle on, sorry guys.

Best regards

Dude

PS Welcome back Landlady, hope you've recovered from your fall XXXX

The first thing I know EXWOK and BELLEROPHON will (maybe) notice is that originally OAD had a 'normal colour' electroluminescent light plate on the visor indication panel. (If I remember rightly (it was a million years ago chaps) when this one 'stopped lighting' we could not get a replacement and had to rob 202 (G-BBDG) at Filton; this one being the same black development aircraft colour that OAD has to this day.

The OTHER first thing that you may notice is the Triple Temperature Indicator on the captains dash panel. (The first officer had his in in similar position). These got moved around (twice in the end) when TCAS was installed in the mid-90's. It was amazing just how much equipment got moved around over the years, in order to 'shoe-horn in' various bits of extra equimpent.

The cabin altimeter here fitted just above the #1 INS CDU also got moved (to the centre consul) when the FAA 'Branniff' modifications were embodied later in the 70's. It's spot got occupied by a standy altimeter mandated by the FAA but this was removed after Branniff ceased flying Concorde; the cabin altimeter returning to it's former home. The REALLY observant will notice that there is neither an Autoland Ca3/Cat2 identifier on the AFCS panel (glued on by BA at LHR) or the famous and precision built 'Reheat Capabilty Indicator' flip down plate fitted to the centre dash panel a few years later by BA.

Also not shown here, as they were buyer furnished equipment also fitted at on delivery LHR, are the two ADEUs (Automatic Data Entry Units, or INS Card readers). These were located immediatel aft of the CDU's and were used for bulk waypoint loading ('bulk' being 9, the most that the poor old Delco INU memory could handle). These were removed in the mid 90's when the Navigation Database was fitted to Concorde INUs, and bulk loading then was achieved by simply tapping in a 2 digit code. (Hardly the elegence of FMS, but still very elegent in comparison with the ADEU's, and worked superbly). A little note about these ADEU things; You inserted this rather large optically read paper data card into the thing and the motor would suck the unsuspecting card in. As often as not the ADEU would chew the card up and spit the remnants out, without reading any data, or not even bother spitting out the remnants at all. Removing these things FINALLY when the INUs were modified was absolute joy!!

ps. When G-BOAG (then G-BFKW) was delivered in 1980 it had neither any of the Branniff mods or ADEUs fitted. (Also the INS was not wired for DME updating). This meant that obviously she could not fly IAD-DFW with Branniff but also she could not do LHR-BAH either, because of the lack ADEUs. (You could not manually insert waypoints quick enough over the 'Med', or so the guys told me. So for the first few years good old FKW/OAG just used to plod between LHR and JFK. And plod she did, superbly. She never did get the ADEUs (not necessary thank goodness when the INUs got modified) but we wired in DME updating and so she could navigate around with the best of them.

My gosh I do prattle on, sorry guys.

Best regards

Dude

PS Welcome back Landlady, hope you've recovered from your fall XXXX

Last edited by M2dude; 15th Jan 2011 at 11:29 .

8th Feb 2011, 17:43

permalink Post: 1182

Quote:

|

I am looking at my office wall in Fremantle, Western Australia at a photograph of G-BOAC after getting airbourne on its maiden flight. It is signed by my work colleges at Brooklands.

|

In my case it's a pic of G-BSST, signed by colleages and friends at Fairford.

Has been hanging over my desks in France for over 35 years, and hasn't really bleached yet.... good quality colour print....

Quote:

| Somewhere in a trunk I have a copy (blueprint) of prototype 01 notated in both English and French. |

And yes, most are annotated in both French and English, both the descriptive legends and the measurements (i.e., metric and 'imperial').

CJ

18th Apr 2011, 05:06

permalink Post: 1301

Well in that case you are obviously right I suppose and BA, BAe (as it was) and the CAA were all wrong as far as component 30 goes. And everything that I was told at Fairford was wrong too. I guess it goes to show I suppose that all these bodies can be wrong.

There were several semi-structural and 'heavy' system components that were robbed by BA (I removed some stuff myself in the mid 80's and early 90's), but the fact remains that there were massive system differences that could never be reconciled by simple 'mods'. The fact also remains that she was a 5100 variant aircraft and not a 5101/5102 variant (or a 100 series aircraft either) and was significantly D-I-F-F-E-R-E-N-T to the 'real' aircraft, the airliners. I was THERE and I SAW the differences myself enough times for goodness sake, and the fact remains she was NEVER an airliner and never had any real prospect of being one. (But as I said before, she was a wonderful TEST specimin and did some stirling work). Brooklands really has a lot to offer the visitor as an exhibit I suppose but if you want to see Concorde THE AIRLINER then you really need to go elsewhere. Manchester in the only place where you can now see an intact production series Concorde in the UK and as I said before is NOW lovingly cared for by some brilliant people.

Regards

Dude

There were several semi-structural and 'heavy' system components that were robbed by BA (I removed some stuff myself in the mid 80's and early 90's), but the fact remains that there were massive system differences that could never be reconciled by simple 'mods'. The fact also remains that she was a 5100 variant aircraft and not a 5101/5102 variant (or a 100 series aircraft either) and was significantly D-I-F-F-E-R-E-N-T to the 'real' aircraft, the airliners. I was THERE and I SAW the differences myself enough times for goodness sake, and the fact remains she was NEVER an airliner and never had any real prospect of being one. (But as I said before, she was a wonderful TEST specimin and did some stirling work). Brooklands really has a lot to offer the visitor as an exhibit I suppose but if you want to see Concorde THE AIRLINER then you really need to go elsewhere. Manchester in the only place where you can now see an intact production series Concorde in the UK and as I said before is NOW lovingly cared for by some brilliant people.

Regards

Dude

Last edited by M2dude; 18th Apr 2011 at 08:05 .

8th May 2013, 16:05

permalink Post: 1714

For the french speaking (or reading) people here, I just found a mine of very interesting informations about Concorde on this website:

Accueil

This site has a database of thousand of concorde flights with the following datas: Date and time of the flight, airframe used, technical and commercial crews, guests, departure/arrival airports and flight type (regular, charter world tour...).

On top of that, many infos and stories around Concorde can also be found there.

I can't resist to translate one of those stories (I'm far from being a native english speaker or a professional translator; so forgive me for the misspellings and other translation mistakes). It is a report about one of the biggest incident that happened to the prototype 001 during the flight tests:

Shock of shockwaves

We were flying with Concorde at Mach 2 since 3 month already on both side of the Channel. The prototype 001 did outstrip 002 which was supposed to be the first to reach Mach 2.

Unfortunately, a technical issue delayed 002 and Brian Trubshaw fairly let Andr\xe9 Turcat be the first to reach Mach 2 with the 001 which was ready to go.

The flight tests were progressing fast and we were discovering a part of the atmosphere that military aircrafts hardly reached before. With Concorde, we were able to stay there for hours although limited by the huge fuel consumption of the prototypes.

The Olympus engines did not reached their nominal performance yet and, most of the time, we had to turn on the reheat in supersonic cruise to maintain Mach 2.

The reheat is what we call afterburner on military aircrafts. Fuel is injected between the last compressor stage of the low pressure turbine and the first exhaust nozzle. This increases the thrust for the whole engine and its nozzle.

The 4 reheats, one for each engine, are controlled by the piano switches behind the thrust leavers on the center pedestal between the two pilots. Air was fed into the engines through 4 air intakes, one for each engine, attached 2 by 2 to the 2 engine nacelle, one under each wing. The advantage in terms of drag reduction was obvious.

However, tests in wind tunnel showed that, at supersonic speed, if a problem happens on one engine, there was a great chance for the adjacent engine to be affected as well by the shockwave interference from one air intake to the other despite the presence the dividing wall between the two intakes. So we knew that an engine failure at mach 2 would result in the loss of 2 engines on the same side, resulting in a lateral movement leading to a strong sideslip that would likely impact the 2 remaining engines and transform the aircraft into the fastest glider in the world.

This is why an automatic anti sideslip device was developed and installed on the aircrafts.

The air intakes are very sophisticated. At mach 2, it creates a system of shockwaves that slows down the air from 600 m/sec in front of the aircraft to 200 m/sec in front of the engine while maintaining a very good thermodynamic performance. In supersonic cruise, the engines, operating at full capacity all the time, were sensitive to any perturbation and reacted violently with engine surge: the engine refusing the incoming air.

Stopping suddenly a flow of almost 200kg of air per second traveling at 600m/sec causes a few problems. As a result, a spill door was installed under the air intake and automatically opened in such event.

To control the system of shockwaves and obtain an efficiency of 0,96 in compression in the air intake, 2 articulated ramps, controlled by hydraulic jacks, are installed on the top of the air intakes in front of the engines. Each ramp is roughly the size of a big dining room table, and the 2 ramps, mechanically synchronized, move up or down following the instruction of an highly sophisticated computer that adapts the ramp position according to the mach number, the engine rating and other parameters such as skidding.

At that time, it was the less known part of the aircraft, almost only designed through calculation since no simulator, no wind tunnel, did allow a full scale test of the system.

The control of the system was analog and very complex but it was not easy to tune and we were moving ahead with a lot of caution in our test at mach 2.

On the 26th of January 1971, we were doing a nearly routine flight to measure the effect of a new engine setting supposed to enhance the engine efficiency at mach 2. It was a small increase of the rotation speed of the low pressure turbine increasing the air flow and, as a result, the thrust.

The flight test crews now regularly alternate their participation and their position in the cockpit for the pilots.

Today, Gilbert Defer is on the left side, myself on the right side, Michel R\xe9tif is the flight engineer, Claude Durand is the main flight engineer and Jean Conche is the engine flight engineer. With them is an official representative of the flight test centre, Hubert Guyonnet, seated in the cockpit's jump seat, he is in charge of radio testing.

We took off from Toulouse, accelerated to supersonic speed over the Atlantic near Arcachon continuing up to the north west of Ireland.

Two reheats, the 1 and the 3, are left on because the air temperature does not allow to maintain mach 2 without them.

Everything goes fine. During the previous flight, the crew experienced some strong turbulence, quite rare in the stratosphere and warned us about this. No problem was found on the aircraft.

We are on our way back to Toulouse off the coast of Ireland. Our program includes subsonic tests and we have to decelerate.

Gilbert is piloting the aircraft. Michel and the engineers notify us that everything is normal and ready for the deceleration and the descent.

We are at FL500 at mach 2 with an IAS of 530 kt, the maximum dynamic pressure in normal use.

On Concorde, the right hand seat is the place offering the less possibility to operate the systems. But here, we get busy by helping the others to follow the program and the checklists and by manipulating the secondary commands such as the landing gear, the droop nose, the radio navigation, comms, and some essential engine settings apart from the thrust leavers such as the reheat switches.

The normal procedure consists in stopping the reheat before lowering the throttle.

Gilbert asks me to do it. After, he will slowly reduce the throttle to avoid temporary heckler. Note that he did advise us during the training on the air intake to avoid to move the thrust leaver in case of engine surge.

As a safety measure, I shut down the reheat one by one, checking that everything goes fine for each one. Thus I switch off the reheat 1 with the light shock marking the thrust reduction. Then the 3\x85

Instantly, we are thrown in a crazy situation.

Deafening noise like a canon firing 300 times a minute next to us. Terrible shake. The cockpit, that looked like a submarine with the metallic and totally opaque visor obviously in the upper position, is shaken at a frequency of 5 oscillation a second and a crazy amplitude of about 4 to 5 G. To the point that we cannot see anymore, our eyes not being able to follow the movements.

Gilbert has a test pilot reaction, we have to get out of the maximum kinetic energy zone as fast as possible and to reduce speed immediately. He then moves the throttle to idle without any useless care.

During that time, I try, we all try to answer the question: what is going on? What is the cause of this and what can we do to stop it?

Suspecting an issue with the engines, I try to read the indicators on the centre control panel through the mist of my disturbed vision and in the middle of a rain of electric indicators falling from the roof. We cannot speak to each other through the intercom.

I vaguely see that the engines 3 and 4 seem to run slower than the 2 others, especially the 4. We have to do something. Gilbert is piloting the plane and is already busy. I have a stupid reaction dictated by the idea that I have to do something to stop that, while I can only reach a few commands that may be linked to the problem.

I first try to increase the thrust on number 4 engine. No effect so I reduce frankly and definitively. I desperately look for something to do from my right hand seat with a terrible feeling of being helpless and useless.

Then everything stops as suddenly as it started. How long did it last, 30 seconds, one minute?

By looking at the flight data records afterward, we saw that it only last\x85 12 seconds!

However, I have the feeling that I had time to think about tons of things, to do a lot of reasoning, assumption and to have searched and searched and searched\x85! It looked like my brain suddenly switched to a fastest mod of thinking. But, above all, it's the feeling of failure, the fact that I was not able to do anything and that I did not understand anything that remains stuck in my mind forever.

To comfort me, I have to say that nobody among the crew did understand anything either and was able to do anything, apart from Gilbert.

The aircraft slows down and the engine 3 that seemed to have shut down restart thanks to the auto ignition system. But the 4 is off indeed.

Michel makes a check of his instruments. He also notes that the engine 4 has shut down but the 4 air intakes work normally, which makes us feel better. After discussing together, we start to think that we probably faced some stratospheric turbulence of very high intensity, our experience in this altitude range being quite limited at that time. But nobody really believes in this explanation. Finally, at subsonic speed, mach 0.9, with all instruments looking normal, we try to restart engine 4 since we still have a long way to go to fly back to Toulouse.

Michel launches the process to restart the engine. It restarts, remains at a medium rotation speed and shuts down after 20 seconds, leaving us puzzled and a bit worried despite the fact that the instrument indicators are normal.

Gilbert then decide to give up and won't try to restart this engine anymore and Claude leaves his engineer station to have a look in a device installed on the prototype to inspect the landing gear and the engines when needed: an hypo-scope, a kind of periscope going out through the floor and not through the roof.

After a few seconds, we can hear him on the intercom:

"Shit! (stuttering) we have lost the intake number 4."

He then describes a wide opening in the air intake, the ramp seems to be missing and he can see some structural damages on the nacelle.

Gilbert reacts rapidly by further reducing the speed to limit even more the dynamic pressure.

But we don't know exactly the extent of the damage. Are the wing and the control surfaces damaged? What about engine 3?

We decide to fly back at a speed of 250 kts at a lower altitude and to divert toward Fairford where our british colleagues and the 002 are based. I inform everybody about the problem on the radio and tell them our intentions. However, I add that if no other problems occur, we will try to reach Toulouse since we still have enough fuel.

Flying off Fairford, since nothing unusual happened, we decide to go on toward Toulouse. All the possible diversion airport on the way have been informed by the flight test centre who follows us on their radar.

At low speed, knowing what happened to us and having nothing else to do but to wait for us, time passes slowly, very slowly and we don't talk much, each one of us thinking and trying to understand what happened. However, we keep watching closely after engine 3.

Personally, I remember the funny story of the poor guy who sees his house collapse when he flushes his toilets. I feel in the same situation.

Gilbert makes a precautionary landing since we don't rely much on engine 3 anymore. But everything goes fine.

At the parking, there is a lot of people waiting for us and, as soon as the engines stop, we can see a big rush toward the nacelles of the right hand side engines.

Gilbert and myself are the first to get off the plane and we are welcomed down the stairs by Andr\xe9 Turcat and Jean Franchi who came out from the crowd watching at the right hand side nacelle.

They both behave the same way, with a slow pace attitude, the same look, a mix of disbelief and frustration.

Andr\xe9 is the first to speak: "I can't believe we were not on this flight, really unlucky\x85". Yes, this flight was supposed to be just a routine flight\x85!

The condition of the nacelle is impressive. We come closer and everybody move aside for us with a look of disbelief and respect as if we were hell survivors.

The ramps of the intake 4, those 2 "dining tables", have completely disappeared leaving a hole where we can see the hydraulic jacks and the stub rod where the ramps were attached.

Indeed, only the ramps were missing, apparently ejected forward which was unbelievable knowing how fast we were flying. The ramp slipped under the nacelle causing some damages on it and on the hood of one of the elevon's servo control. Fortunately, the control did not suffer any damage.

What is left of the rear ramp seems to be blocked down inside the intake in front of the engine and we can see behind it the first blades of the compressor, or what is left of it, not much.

The engine swallowed a huge amount of metal but no vital parts of the aircraft has been damaged, no hydraulic leaks, no fuel leaks. I remembered at that time the stories of some B58 Hustler accident where the loss of an engine at mach 2 almost certainly ended with the complete loss of the aircraft. Our Concorde has only been shaken. This incident strengthened the trust I had in this plane. And I was not unhappy to have experienced this ordeal, especially when I saw the frustration on the face of Andr\xe9 Turcat and Jean Franchi.

But we had to understand what happened and how; and also why the ramp's fixing broke.

It didn't take much time to get the answers.

I unintentionally triggered the problem when shutting down the reheat of engine 3. The sudden stop of the fuel flow did of course stop the combustion and the back pressure behind the low pressure turbine. But, probably because of the modification made on the engine before the flight, the stop of the reheat has not been followed by the normal closing movement of the primary nozzle to compensate the pressure drop. So the low pressure turbine ran out of control, dragging down the low pressure compressor which reacts by surging.

Despite the opening of the spill door, the engine surge led to a sudden movement of the shockwaves in the air intake creating a surge in the intake itself. A similar surge happened in the adjacent intake 4 followed by a surge of the corresponding engine. This caused an excessive pressure above the ramps and the fixings of the intake 4 did not hold.

Since it was the first time we experienced a surge in the air intake, we had little knowledge of the stress it would create on the ramps. This led to miscalculation of the strength of the ramps's frames and they did brake.

Another mistake: instead of installing the motion detectors on the ramp itself, to make the production easier, they have been placed on the arms of the hydraulic jacks. This is why Michel R\xe9tif thought that the position of the ramps were correct. The hydraulic jacks did not suffer any damage and were still working normally even if the ramps were missing.

All the data recorded during this event helped us in redesigning the air intakes and the flight test program resumed three month later.

After this, we deliberately created dozen and dozen of air intake surge to fine tune the way to regulate them with digital calculator this time.

From now on, even if it was still very impressive, it was safe and their intensity was not comparable with what we experienced with the missing ramps.

However, a french president may kept a lasting memory of this, much later, during a flight back from Saudi Arabia. This time, I was on the left side, Gilbert on the right and Michel was still in the third seat\x85 But that's another story.

For me, the lasting impression of failing and being helpless during this incident made me wonder what a commercial pilot would have done in this situation. This plane was designed to be handled by standard commercial pilots and not only by the flight test pilots.

At that time, I was interested in taking in charge the management of a training center for the pilots of the future Airbus's clients. This event pushed me that way and I made it clear that I wanted to add the flight training on Concorde in this project. This has been agreed and I did it.

And the Concorde training program now covers the air intake surges and how to deal with them.

Jean PINET

Former test pilot

Member and former president of the Air and Space Academy

Accueil

This site has a database of thousand of concorde flights with the following datas: Date and time of the flight, airframe used, technical and commercial crews, guests, departure/arrival airports and flight type (regular, charter world tour...).

On top of that, many infos and stories around Concorde can also be found there.

I can't resist to translate one of those stories (I'm far from being a native english speaker or a professional translator; so forgive me for the misspellings and other translation mistakes). It is a report about one of the biggest incident that happened to the prototype 001 during the flight tests:

Shock of shockwaves

We were flying with Concorde at Mach 2 since 3 month already on both side of the Channel. The prototype 001 did outstrip 002 which was supposed to be the first to reach Mach 2.

Unfortunately, a technical issue delayed 002 and Brian Trubshaw fairly let Andr\xe9 Turcat be the first to reach Mach 2 with the 001 which was ready to go.

The flight tests were progressing fast and we were discovering a part of the atmosphere that military aircrafts hardly reached before. With Concorde, we were able to stay there for hours although limited by the huge fuel consumption of the prototypes.

The Olympus engines did not reached their nominal performance yet and, most of the time, we had to turn on the reheat in supersonic cruise to maintain Mach 2.

The reheat is what we call afterburner on military aircrafts. Fuel is injected between the last compressor stage of the low pressure turbine and the first exhaust nozzle. This increases the thrust for the whole engine and its nozzle.

The 4 reheats, one for each engine, are controlled by the piano switches behind the thrust leavers on the center pedestal between the two pilots. Air was fed into the engines through 4 air intakes, one for each engine, attached 2 by 2 to the 2 engine nacelle, one under each wing. The advantage in terms of drag reduction was obvious.

However, tests in wind tunnel showed that, at supersonic speed, if a problem happens on one engine, there was a great chance for the adjacent engine to be affected as well by the shockwave interference from one air intake to the other despite the presence the dividing wall between the two intakes. So we knew that an engine failure at mach 2 would result in the loss of 2 engines on the same side, resulting in a lateral movement leading to a strong sideslip that would likely impact the 2 remaining engines and transform the aircraft into the fastest glider in the world.

This is why an automatic anti sideslip device was developed and installed on the aircrafts.

The air intakes are very sophisticated. At mach 2, it creates a system of shockwaves that slows down the air from 600 m/sec in front of the aircraft to 200 m/sec in front of the engine while maintaining a very good thermodynamic performance. In supersonic cruise, the engines, operating at full capacity all the time, were sensitive to any perturbation and reacted violently with engine surge: the engine refusing the incoming air.

Stopping suddenly a flow of almost 200kg of air per second traveling at 600m/sec causes a few problems. As a result, a spill door was installed under the air intake and automatically opened in such event.

To control the system of shockwaves and obtain an efficiency of 0,96 in compression in the air intake, 2 articulated ramps, controlled by hydraulic jacks, are installed on the top of the air intakes in front of the engines. Each ramp is roughly the size of a big dining room table, and the 2 ramps, mechanically synchronized, move up or down following the instruction of an highly sophisticated computer that adapts the ramp position according to the mach number, the engine rating and other parameters such as skidding.

At that time, it was the less known part of the aircraft, almost only designed through calculation since no simulator, no wind tunnel, did allow a full scale test of the system.

The control of the system was analog and very complex but it was not easy to tune and we were moving ahead with a lot of caution in our test at mach 2.

On the 26th of January 1971, we were doing a nearly routine flight to measure the effect of a new engine setting supposed to enhance the engine efficiency at mach 2. It was a small increase of the rotation speed of the low pressure turbine increasing the air flow and, as a result, the thrust.

The flight test crews now regularly alternate their participation and their position in the cockpit for the pilots.

Today, Gilbert Defer is on the left side, myself on the right side, Michel R\xe9tif is the flight engineer, Claude Durand is the main flight engineer and Jean Conche is the engine flight engineer. With them is an official representative of the flight test centre, Hubert Guyonnet, seated in the cockpit's jump seat, he is in charge of radio testing.

We took off from Toulouse, accelerated to supersonic speed over the Atlantic near Arcachon continuing up to the north west of Ireland.

Two reheats, the 1 and the 3, are left on because the air temperature does not allow to maintain mach 2 without them.

Everything goes fine. During the previous flight, the crew experienced some strong turbulence, quite rare in the stratosphere and warned us about this. No problem was found on the aircraft.

We are on our way back to Toulouse off the coast of Ireland. Our program includes subsonic tests and we have to decelerate.

Gilbert is piloting the aircraft. Michel and the engineers notify us that everything is normal and ready for the deceleration and the descent.

We are at FL500 at mach 2 with an IAS of 530 kt, the maximum dynamic pressure in normal use.

On Concorde, the right hand seat is the place offering the less possibility to operate the systems. But here, we get busy by helping the others to follow the program and the checklists and by manipulating the secondary commands such as the landing gear, the droop nose, the radio navigation, comms, and some essential engine settings apart from the thrust leavers such as the reheat switches.

The normal procedure consists in stopping the reheat before lowering the throttle.

Gilbert asks me to do it. After, he will slowly reduce the throttle to avoid temporary heckler. Note that he did advise us during the training on the air intake to avoid to move the thrust leaver in case of engine surge.

As a safety measure, I shut down the reheat one by one, checking that everything goes fine for each one. Thus I switch off the reheat 1 with the light shock marking the thrust reduction. Then the 3\x85

Instantly, we are thrown in a crazy situation.

Deafening noise like a canon firing 300 times a minute next to us. Terrible shake. The cockpit, that looked like a submarine with the metallic and totally opaque visor obviously in the upper position, is shaken at a frequency of 5 oscillation a second and a crazy amplitude of about 4 to 5 G. To the point that we cannot see anymore, our eyes not being able to follow the movements.

Gilbert has a test pilot reaction, we have to get out of the maximum kinetic energy zone as fast as possible and to reduce speed immediately. He then moves the throttle to idle without any useless care.

During that time, I try, we all try to answer the question: what is going on? What is the cause of this and what can we do to stop it?

Suspecting an issue with the engines, I try to read the indicators on the centre control panel through the mist of my disturbed vision and in the middle of a rain of electric indicators falling from the roof. We cannot speak to each other through the intercom.

I vaguely see that the engines 3 and 4 seem to run slower than the 2 others, especially the 4. We have to do something. Gilbert is piloting the plane and is already busy. I have a stupid reaction dictated by the idea that I have to do something to stop that, while I can only reach a few commands that may be linked to the problem.

I first try to increase the thrust on number 4 engine. No effect so I reduce frankly and definitively. I desperately look for something to do from my right hand seat with a terrible feeling of being helpless and useless.

Then everything stops as suddenly as it started. How long did it last, 30 seconds, one minute?

By looking at the flight data records afterward, we saw that it only last\x85 12 seconds!

However, I have the feeling that I had time to think about tons of things, to do a lot of reasoning, assumption and to have searched and searched and searched\x85! It looked like my brain suddenly switched to a fastest mod of thinking. But, above all, it's the feeling of failure, the fact that I was not able to do anything and that I did not understand anything that remains stuck in my mind forever.

To comfort me, I have to say that nobody among the crew did understand anything either and was able to do anything, apart from Gilbert.

The aircraft slows down and the engine 3 that seemed to have shut down restart thanks to the auto ignition system. But the 4 is off indeed.

Michel makes a check of his instruments. He also notes that the engine 4 has shut down but the 4 air intakes work normally, which makes us feel better. After discussing together, we start to think that we probably faced some stratospheric turbulence of very high intensity, our experience in this altitude range being quite limited at that time. But nobody really believes in this explanation. Finally, at subsonic speed, mach 0.9, with all instruments looking normal, we try to restart engine 4 since we still have a long way to go to fly back to Toulouse.

Michel launches the process to restart the engine. It restarts, remains at a medium rotation speed and shuts down after 20 seconds, leaving us puzzled and a bit worried despite the fact that the instrument indicators are normal.

Gilbert then decide to give up and won't try to restart this engine anymore and Claude leaves his engineer station to have a look in a device installed on the prototype to inspect the landing gear and the engines when needed: an hypo-scope, a kind of periscope going out through the floor and not through the roof.

After a few seconds, we can hear him on the intercom:

"Shit! (stuttering) we have lost the intake number 4."

He then describes a wide opening in the air intake, the ramp seems to be missing and he can see some structural damages on the nacelle.

Gilbert reacts rapidly by further reducing the speed to limit even more the dynamic pressure.

But we don't know exactly the extent of the damage. Are the wing and the control surfaces damaged? What about engine 3?

We decide to fly back at a speed of 250 kts at a lower altitude and to divert toward Fairford where our british colleagues and the 002 are based. I inform everybody about the problem on the radio and tell them our intentions. However, I add that if no other problems occur, we will try to reach Toulouse since we still have enough fuel.

Flying off Fairford, since nothing unusual happened, we decide to go on toward Toulouse. All the possible diversion airport on the way have been informed by the flight test centre who follows us on their radar.

At low speed, knowing what happened to us and having nothing else to do but to wait for us, time passes slowly, very slowly and we don't talk much, each one of us thinking and trying to understand what happened. However, we keep watching closely after engine 3.

Personally, I remember the funny story of the poor guy who sees his house collapse when he flushes his toilets. I feel in the same situation.

Gilbert makes a precautionary landing since we don't rely much on engine 3 anymore. But everything goes fine.

At the parking, there is a lot of people waiting for us and, as soon as the engines stop, we can see a big rush toward the nacelles of the right hand side engines.

Gilbert and myself are the first to get off the plane and we are welcomed down the stairs by Andr\xe9 Turcat and Jean Franchi who came out from the crowd watching at the right hand side nacelle.

They both behave the same way, with a slow pace attitude, the same look, a mix of disbelief and frustration.

Andr\xe9 is the first to speak: "I can't believe we were not on this flight, really unlucky\x85". Yes, this flight was supposed to be just a routine flight\x85!

The condition of the nacelle is impressive. We come closer and everybody move aside for us with a look of disbelief and respect as if we were hell survivors.

The ramps of the intake 4, those 2 "dining tables", have completely disappeared leaving a hole where we can see the hydraulic jacks and the stub rod where the ramps were attached.

Indeed, only the ramps were missing, apparently ejected forward which was unbelievable knowing how fast we were flying. The ramp slipped under the nacelle causing some damages on it and on the hood of one of the elevon's servo control. Fortunately, the control did not suffer any damage.

What is left of the rear ramp seems to be blocked down inside the intake in front of the engine and we can see behind it the first blades of the compressor, or what is left of it, not much.

The engine swallowed a huge amount of metal but no vital parts of the aircraft has been damaged, no hydraulic leaks, no fuel leaks. I remembered at that time the stories of some B58 Hustler accident where the loss of an engine at mach 2 almost certainly ended with the complete loss of the aircraft. Our Concorde has only been shaken. This incident strengthened the trust I had in this plane. And I was not unhappy to have experienced this ordeal, especially when I saw the frustration on the face of Andr\xe9 Turcat and Jean Franchi.

But we had to understand what happened and how; and also why the ramp's fixing broke.

It didn't take much time to get the answers.

I unintentionally triggered the problem when shutting down the reheat of engine 3. The sudden stop of the fuel flow did of course stop the combustion and the back pressure behind the low pressure turbine. But, probably because of the modification made on the engine before the flight, the stop of the reheat has not been followed by the normal closing movement of the primary nozzle to compensate the pressure drop. So the low pressure turbine ran out of control, dragging down the low pressure compressor which reacts by surging.

Despite the opening of the spill door, the engine surge led to a sudden movement of the shockwaves in the air intake creating a surge in the intake itself. A similar surge happened in the adjacent intake 4 followed by a surge of the corresponding engine. This caused an excessive pressure above the ramps and the fixings of the intake 4 did not hold.

Since it was the first time we experienced a surge in the air intake, we had little knowledge of the stress it would create on the ramps. This led to miscalculation of the strength of the ramps's frames and they did brake.

Another mistake: instead of installing the motion detectors on the ramp itself, to make the production easier, they have been placed on the arms of the hydraulic jacks. This is why Michel R\xe9tif thought that the position of the ramps were correct. The hydraulic jacks did not suffer any damage and were still working normally even if the ramps were missing.

All the data recorded during this event helped us in redesigning the air intakes and the flight test program resumed three month later.

After this, we deliberately created dozen and dozen of air intake surge to fine tune the way to regulate them with digital calculator this time.

From now on, even if it was still very impressive, it was safe and their intensity was not comparable with what we experienced with the missing ramps.

However, a french president may kept a lasting memory of this, much later, during a flight back from Saudi Arabia. This time, I was on the left side, Gilbert on the right and Michel was still in the third seat\x85 But that's another story.

For me, the lasting impression of failing and being helpless during this incident made me wonder what a commercial pilot would have done in this situation. This plane was designed to be handled by standard commercial pilots and not only by the flight test pilots.

At that time, I was interested in taking in charge the management of a training center for the pilots of the future Airbus's clients. This event pushed me that way and I made it clear that I wanted to add the flight training on Concorde in this project. This has been agreed and I did it.

And the Concorde training program now covers the air intake surges and how to deal with them.

Jean PINET

Former test pilot

Member and former president of the Air and Space Academy

Last edited by NHerby; 9th May 2013 at 17:24 .